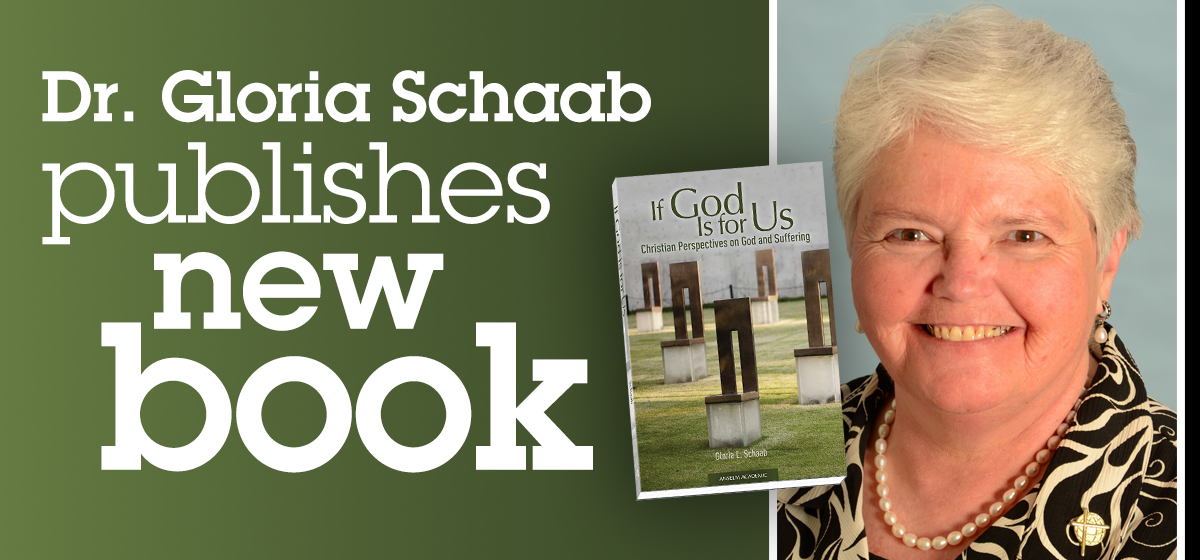

How can God permit misery and suffering in an individual or group of people if God is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-loving, as most believe God to be? A new book by Barry University Associate Professor of Theology, Gloria L. Schaab, SSJ, PhD, examines this question from many individual viewpoints and different Christian perspectives.

“No experience in human life provokes more questions about who God is and how God relates to us than the experience of suffering in the world. Whether it is suffering that affects us personally — or it is the immense suffering of peoples throughout the world — the questions always arise of who God is, how God acts, and where God is in the midst of suffering,” says Dr. Schaab, author of “If God Is for Us: Christian Perspectives on God and Suffering.”

“I wrote this book in the hope that students and other readers might find in it some way to understand and encounter a God who is for them and with them in their suffering,” says Dr. Schaab, of the Theology & Philosophy Department, College of Arts and Sciences, at Barry University in South Florida.

Wide Ranging and Inclusive

Dr. Schaab designed the book for a course she created at Barry University: “THE 308: God and Suffering in the Jewish and Christian Traditions.” However, the insights in the text play to wider audiences.

The question of God and suffering is one that every religious tradition must face and attempt to answer, Dr. Schaab says. “For me, I believe [it] is the most important question that a theologian or a minister must attempt to answer — because it is the question that can either draw people closer to God or can drive them away from God.”

Dr. Schaab considered whether the book would ring true with her Barry University students throughout the writing process. For this reason, readers gain theological perspectives from a range of social and cultural contexts, ones that reflect the diversity of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and religion in the student body.

“People’s suffering often arises from their exclusion, marginalization or oppression because of gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability,” she says.

What Dr. Schaab Learned

Researching a text intended for advanced theology students can yield some unexpected findings. “Perhaps I was most ‘surprised’ by research on theologies of disabilities,” Dr. Schaab says. Admittedly less familiar with this area, she expected that the theology of suffering would center upon the physical impairment itself. “However, I soon learned that theologies of disability stemmed not from impairment per se, but rather from the personal, social, occupational and structural marginalization that persons with impairments experience.”

As the Union of the Physically Impaired against Segregation states, “Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society.”

Dr. Schaab says, “This was a significant and compelling insight for me.”

Finding Hope and Compassion

The book doesn’t stop at examining suffering from multiple viewpoints. It explains that there are many ways of understanding, speaking about and encountering God in the midst of human suffering based on Scripture and the Christian tradition.

Importantly, readers are encouraged to consider various theological responses. “No one Christian theological perspective provides the ultimate answer; each has possibilities and problems; each has strengths and limitations for those who seek God in the midst of suffering.”

Instead, Dr. Schaab hopes that students “take the opportunity to think through the various Christian theologies – each grounded in scripture, tradition, and human experience – and evaluate them through their own reflection and human experience.” The ultimate goal, she adds, is that students discover “a God who ‘is for us’ in our suffering, a God in whom those who suffer can find compassion and hope.”